The Waihora Ellesmere Trust held it’s 2019 AGM on the 16th of September.

The Trust was very privileged to have Allanah Purdie Biodiversity Ranger from the Department of Conservation  talking about the Australasian Bittern – See her presentation here.

talking about the Australasian Bittern – See her presentation here.

Following are the notes from Allanah’s talk:

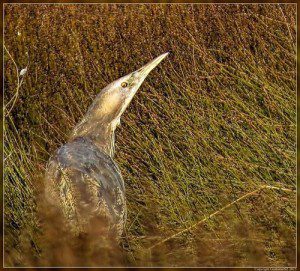

The Australasian Bittern – Matuku are a large, wetland bird.

They are native, and although they are also found in Australia, total population numbers are very low. It is optimistically estimated that there are fewer than 1000 birds in both Australia & New Zealand.

In 2016 their threat status rose to Nationally Critical, making them more threatened than other more well-known species such as brown kiwi, kokako and whio.

Matuku are specialist feeders that rely heavily on their sight, they need clear, shallow water in which to stalk their prey. They feed mostly on small fish and eels but will eat whatever they can stab, such as worms, spiders and frogs.

Although a large bird, they are highly cryptic. They are secretive and often rely on their excellent camouflage and ‘freeze’ stance to imitate the reeds and raupo they live in. Today, they are found in relatively low densities and range far and wide in search of feeding habitat. This makes them very hard to monitor.

Te Waihora is a significant site for bittern and always has been, Maori oral history records show large flocks and cite the birds as a common food source.

Unfortunately, as with many of our native species there is a recorded decline of bittern following European occupation, with the most rapid decline in Canterbury occurring over the last hundred years.

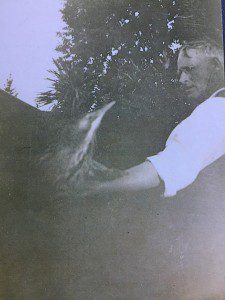

This image (slide three) was taken in the 1930s of Lynette Harris’ Grandfather Jack Harris at their farm near Pannetts Road. This was a time when bittern were still common compared to today’s numbers. The current estimate for the whole of New Zealand sits below 1000.

So why is Te Waihora still considered a stronghold for the bittern?

The lake has extensive shallow water and reed beds as well as numerous small fish and eel species which bittern prefer. There are also other good foraging habitats such as Coopers Lagoon and Wairewa within easy flying distance for a bittern.

This extent of foraging habitat means that there is always suitable hunting ground for the highly mobile birds. There are also suitable nesting habitats around the lake which make it a very valuable territory to hold.

The enormous and sparse nature of the lake is also very beneficial for this shy bird. The large portions of lake margin that are inaccessible by people and the general low inhabitants of the lake, mean the bittern can get on with foraging free of interruption. And Te Waihora still exists! With the loss of most Wetlands in Canterbury and NZ, the lake is a stronghold for bittern purely because where else would they go?

Pre 2014 little was known about bittern in Canterbury. We didn’t know how many we had, where they were or what the population was doing. Very little was known about the bird’s ecology, causes of decline and how we might go about managing their populations in Canterbury. What we did know though was that other strongholds around the country were observing steep declines.

Pre 2014 little was known about bittern in Canterbury. We didn’t know how many we had, where they were or what the population was doing. Very little was known about the bird’s ecology, causes of decline and how we might go about managing their populations in Canterbury. What we did know though was that other strongholds around the country were observing steep declines.

Whangamarino wetland in the North Island had observed an 89% decline over just 35 years. Under the umbrella of Arawai Kakariki, the bittern project in Canterbury started, generously funded by Ecan and managed by DOC.

It started small with a few key people such as Frances Schmechel from Ecan, Colin O’Donnell and Anita Spencer from DOC, and Emma Williams and Peter Langlands as local bittern experts. Needless to say, the project has grown and evolved based on what us being found out. We quickly came to terms with the fact that locating and keeping tabs on these birds is tricky so that is where a lot of this project has been focused. Because, how do we know if our management techniques are working if we can’t find the birds and measure their success or decline?

One thing we did know was that Harts Creek was a significant site for bittern, so a predator trapline was established right away. The idea with this line was to ring fence the bittern habitat and target key predators that could be affecting the breeding success. Since installing the trapline of more than 50 traps at Harts Creek, we have removed just shy of 400 predators, including 150 hedgehogs, 33 stoats, 11 ferrets and 4 cats.

Although this trap rate is a good thing, until recently we were only protecting bittern when they were visiting Harts creek. As a mobile species and with such good habitat elsewhere around the lake it was obvious that with an increase in funds, we would begin to set up traplines at other key bittern areas.

This year we have set up lines at Halswell river mouth and Lakeside reserve. This, combined with other groups efforts such as the Waihora Ellesmere’s new trapline at Yarrs Flat…who knows, soon we could have the whole lake ring fenced with traps.

But without having adequate information on our illusive bittern, how do we know that all this trapping is having a positive effect? Thankfully, as part of another joint ECan DOC venture, Dr Emma Williams is exploring the use of Marsh and Spotless Crake as an indicator species for bittern. That’s another 20 minute talk entirely but its some exciting work that is being undertaken around the lake.

What has the bittern project found out so far by monitoring our bittern?

In 2014 call count monitoring was set up at 4 locations around Te Waihora. This involved a few keen people out at dusk during the breeding season in Spring, counting the booming displays of the male bittern. Since then, call monitoring has expanded to also cover sites up near the Waimakariri. And last year the project covered 10 monitoring stations over 6 locations with over a dozen people counting the booms. At the same time, several acoustic recording devices were set at other sites around the lake and coastal wetlands where we knew bittern may be booming and claiming territories. On one monitoring night during October, 10 different locations had booming bittern recorded by our listeners and the acoustic recorders.

So why are we so interested in the booming males?

Well there are multiple reasons:

The rate of booming exhibited by the male is correlated with the number of other bittern in the area. More booms per minute = more bittern present.

We also get important indications of the number of territories held in an area.

By listening night after night to who is booming where, we begin to be able to paint a picture of the territories and therefore how many birds we may have breeding in the area. Bittern have large territories and even though Harts creek is good habitat, it only contained 2 territories last season. It is also important because when booms are heard consistently throughout the breeding season, it is a good indication that there may be an ever-illusive nest within the territory. This becomes important information to have when we are wanting to look at females and breeding success around the lake. Unfortunately, from our annual monitoring we have seen the rate of booming decline year on year at all our Te Waihora sites.

Another method of monitoring bittern is by radio and GPS tagging birds. From tracking their wider movements we can see which areas are the most visited, how far they range in search of resources, where they migrate to in the winter, individual mortality and whether they’re hanging around after localized environmental changes such as the lake opening.

Before we can attach any tags to the birds, we have to trap them. This involves Emma and an unsuspecting helper, out in the Raupo beds with a mirror, a cage and a boom box during lakefly season. Because the bittern males are so territorial, they cannot stand for another male booming within their patch. By using the vegetation to guide the fuming male down a narrow track towards this noisy invader, the boom box, he gets to the cage where the cruel trick of the mirror leads him in to thinking his enemy is standing right there, he then rushes in to fight only to be entrapped by our carefully concealed cage.

This makes trapping the birds sound fool proof and easy, it is not, we do have our fair share of failed capture attempts. So when we do catch one, we make the most of it, the individual caught gets measurements taken, weight and feather samples and of course the attaching of radio, GPS tag or both. Previously, due to dodgy technology and large cost involved birds were not always fitted with both a radio and GPS tag. There are benefits and faults to both and while the GPS tag automatically generates location fixes and uploads them via satellite, they’re expensive and last only a year or so. Whereas the radio tags emit signal for longer periods of time, its time consuming and it is very difficult tracking the mobile bittern outside of the breeding season.

From the birds that were GPS tagged, we have discovered that our Canterbury birds move a really long way! One individual flew all the way from Harts, up to Blenheim where he stayed for the breeding season before flying all the way back. That’s a 620km round trip, the longest trip ever recorded in NZ.

Other tagged birds regularly visited habitat 20+ kms away, from the Rakaia to Pegasus wetland. Although its impressive, this is showing us that for the birds to get the resources they need, they are having to use a really large network of wetlands and travel long distances which will surely be having a negative impact on their health.

Canterbury is not alone in this observation. Across the country, at places like Whangamarino Wetland, birds are travelling over 100km in search of food. A study of 10 male bittern in the Hawkes Bay showed that the birds are commonly utilizing wetlands within a 15km radius.

Although its not part of the Bittern project, I think our program shows why some other projects around Te Waihora, that focus on improving and creating habitat for bittern, are so important. Another DOC Ecan project dubbed ‘the weed strike force’, has a dedicated team working tirelessly on the mammoth task of tackling the willows suffocating the lake margins, I’m sure some of you may have seen them out there in their waders.

The team over the last year have eradicated willows from part of the Northern lake edge meaning they will only need to go back annually to check for re-invasion. They have also made a substantial dent in the willow numbers at sites around the Western lake edge. This same team has also been responsible for over 16,000 trees planted around Te Waihora this season, under the billion trees program.

Projects like the ones at Osbornes drain by Selwyn District Council and Ahuriri Lagoon by Ecan, as well as restoration of the natural lake margin through the gradual recession of grazing, will undoubtedly see a wealth of new foraging habitat available to the bittern based at Te Waihora.

From this season, we hope to look more into developing methods of intentionally trapping and tagging female birds and even tracking down and monitoring their nest outcomes.

Specific things we would like to look at are:

What is the predation rate of bittern nests at Te Waihora?

And who are our biggest threats?

A preliminary study by Emma Williams up at Wairarapa moana looked at the ‘survival’ of fake bittern nests and found that nests were visited by a range of predators, some were even lost due to harriers. This leads us to question, ‘are Harriers a concern for our bittern too?’

What effect does opening the lake have for bittern at Te Waihora?

We know that the nests platforms are constructed so that they sit around 30cm above the water how do the fluctuating water levels effect theses nests? And do we have enough foraging habitat available no matter what level the lake sits at?

We have come a long way in 5 years but we still clearly have so many questions to answer.

So as this season starts, we are poised and ready with GPS tags and a horde of people ready to count the booms for the annual call monitoring and even 2 extra staff who will be on the hunt for females and nests.

This will hopefully provide us with greater knowledge and give us the ability to answer some of our remaining questions.