State of the Lake 2017

State of the Lake 2017

Thanks to everyone who has contributed to this report which tells us about the state of Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere and environs in 2017. You can download a copy here.

The 2107 report is an update to the Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere State of the Lake 2013 and Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere State of the Lake 2015. This year additional sections have been included: City to Lake links, Christchurch City Council, whom joined the Te Waihora Co-Governance Group in 2016; and, In Lake Nutrient Processing, based on research funded by Whakaora Te Waihora and Environment Canterbury examining how Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere processes nitrogen and phosphorus loads entering the lake.

Introduction

The State of the Lake report is written in conjunction with the Living Lake Symposium. The first Living Lake Symposium was held in 2007 partly in response to media reports that the lake was “technically dead”.

The first Symposium had several key objectives:

- To determine the overall state of the lake, by first defining the key value sets, and indicators that could be reported against;

- To suggest future management actions that would address key issues affecting the defined values;

- To provide a forum within which lay individuals, scientists and managers could openly debate issues; and

- To provide a launching pad for integrated and focused future management of the lake and its environs.

Following the first symposium the Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere State of the Lake and Future Management report was published; bringing together the ten principal presentations of the symposium. Subsequently the Living Lake Symposium has been held biennially, 2017 being the sixth, and the State of the Lake Report has been published in 2013, 2015 and 2017.

Governance and management

Many organisations play important roles in the governance and management of Te Waihora and its catchment. These include organisations with a statutory role (namely, Environment Canterbury, Selwyn District Council, Christchurch City Council, Department of Conservation, Ministry for Primary Industries, Fish & Game NZ, and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu), non-statutory organisations, and a range of interest groups whose views are taken into consideration. The catchment of the lake is large and activities throughout the catchment have varying impacts on the lake and it tributaries.

Lake Level management

Te Waihora has no natural outlet to the sea. There has been a long history of opening the lake by breaching Kaitorete Spit. Prior to European settlement Te Wai Pounamu, tribal records/mataurangi indicate tangata whenua made periodic breaches to facilitate fish migration and to reduce flooding at Taumutu. The first written record of the artificial opening was in 1852. From 1868 local farmers began informally opening the lake until the Lake Ellesmere Drainage Board was set up in 1905. Today a National Water Conservation Order (WCO) determines the minimum levels above which the lake can be opened.

| Date opened | Date closed | No. days open | Level open | Level closed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24/07/2015 | 09/08/2015 | 17 | 1.23 | 0.95 |

| 21/09/2015 | 08/10/2015 | 18 | 1.21 | 0.77 |

| 01/07/2016 | 18/07/2016 | 18 | 1.19 | 0.65 |

| 28/09/2016 | 31/10/2016 | 34 | 1.11 | 0.69 |

| 29/06/2017 | 12/07/2017 | 14 | 1.21 | 0.84 |

| 25/07/2017 | 02/09/2017 | 40 | 1.56 | 0.75 |

| 01/10/2017 | – | – | 1.09 | – |

Land

Situated at the bottom of the Selwyn catchment, Te Waihora receives contaminants from its large and predominantly agricultural catchment- what is done on the land impacts the waterways. Ongoing development of farmland and townships in Selwyn District have given rise to four main waterway contaminants that affect the health of Te Waihora and its tributaries: nitrogen, phosphorous, sediment, and microbes such as Escherichia coli. Farmers now have a responsibility to farm within water quality limits. The Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan – Selwyn Te Waihora section, sets these limits for the Selwyn-Waihora catchment. Under new land and water management rules, farms with nitrogen losses which exceed 15 kilograms per hectare per year, or with any part of the property within the Cultural Landscape Values Management and Phosphorous Sediment risk areas in the Selwyn-Waihora catchment, now need a land use consent to farm. Included in this land use consent is a farm environment plan (FEP) with good management practices (GMP) and on-farm limits to meet catchment nitrogen load limits.

Water

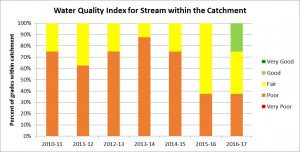

Over all water quality in tributary streams and groundwater have shown improvement in the last two years.  The water quality index has indicated improvements at several sites. This may be a result of land management interventions in the catchment but with dry weather conditions, contaminants may not have been flushed into surface and groundwater systems. A longer monitoring period is required to see if the improving trends are long lasting. However low flows and warmer temperatures have seen a shift in aquatic invertebrate communities with 70% of sites indicating ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ invertebrate grades over the last two years.

The water quality index has indicated improvements at several sites. This may be a result of land management interventions in the catchment but with dry weather conditions, contaminants may not have been flushed into surface and groundwater systems. A longer monitoring period is required to see if the improving trends are long lasting. However low flows and warmer temperatures have seen a shift in aquatic invertebrate communities with 70% of sites indicating ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ invertebrate grades over the last two years.

Vegetation

Wards Wildlife Management Reserve – showing effects of willow control. (Photo Jodi Rees)

Monitoring of vegetation around the margin of Te Waihora is carried out through repeated survey, mapping and description of lakeshore habitats. Data from two surveys, carried out in 1983 and 2007, were analysed and trends reported in the State of Lake 2013. Field survey of Te Waihora shoreline wetlands was repeated in January-April 2017. At the time the 2017 State of the Lake report was being written survey data was being entered into a spatial database. Overall impressions are that the lakeshore vegetation has improved over the last ten years. A reduction of grazing and weed control programmes has helped this response. However, there are parts of the lake shore where indigenous vegetation has declined though clearance, grazing pressure, vehicle damage and the spread of weeds. Initial thoughts from the data was that considerable progress was being make on willow control, however a more complete picture shows that grey willow is still spreading in some areas. Therefore the measure of success for willow control should be closer to the red than green.

Wildlife

The wildlife of Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere is incredibly diverse and includes wetland birds, lizards, and terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates. The overall state for each subset of species has changed little since reporting in 2015. The overall state of native birdlife is good; except for the Australasian crested grebe and Australasian Bittern which have now reached a critical trigger point for management interventions. For at risk lizard, bird, and terrestrial invertebrates species, interventions are in place. Species recovery will be monitored and reported. No improvement is yet occurring for bittern or grebe. For Canterbury mudfish interventions are in place to safeguard the species in the face of drought and predations. There is no active monitoring of ‘ lake flies’, an issue that needs addressing.

Below is a table showing the abundance of indicator bird species during February bird counts from 1985-2017.

| Year | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | NZWS | NZWS/OS | NZWS/OS | OS/CCC | OS/CCC | OS/CCC | WET et al. | WET et al. | WET et al. | WET et al. | WET et al. |

| Australasian Crested Grebe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Black Cormorant | 191 | 150 | 233 | 233 | 254 | 89 | 396 | 615 | 339 | 187 | 212 |

| Australasian Bittern | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 7 | 5 | IP |

| Black Swan | 12682 | 10385 | 5717 | 10006 | 10651 | 9011 | 8598 | 7473 | 5528 | 7186 | 5528 |

| Australasian Shoveler | 6075 | 541 | 263 | 3405 | 1945 | 1161 | 5173 | 5893 | 2070 | 2086 | 1838 |

| Pied Stilt | 2212 | 2067 | 2776 | 2937 | 2566 | 5778 | 3726 | 4959 | 4777 | 3261 | 2821 |

| Wrybill | 38 | 5 | 37 | 230 | 459 | 146 | 429 | 243 | 167 | 216 | 291 |

| Red-necked Stint | 71 | 0 | 99 | 26 | 63 | 18 | 34 | 44 | 31 | 23 | 45 |

| Caspian Tern | 18 | 18 | 15 | 63 | 38 | 96 | 405 | 386 | 113 | 115 | 91 |

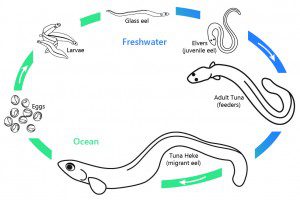

Life cycle of shortfin (Anguilla australis) and longfin (Anguilla dieffenbachii) eels

Fish

Almost 50 fish species have been record from Te Waihora making it amongst the highest recorded fish diversity of any lake in New Zealand. This high number is in part to the occasional influx of nearly 30 marine species. The influx of both freshwater and marine species occurs when the lake is open to the sea and fishes migrate into and out of the lake. These migrations are essential for some species to complete their life cycle and to sustain the fishery in the lake. Both long fin and short fin eels begin and end their life cycle in the ocean. They enter the lake as juveniles (elvers) and after growing for 20-40 years in the lake they return to the ocean to spawn and die.

Economy

A large proportion of the Selwyn District, including all of the more intensively farmed and urban residential areas lies within the catchment of Te Waihora. Selwyn’s annual population growth has been the highest in the country over the pass decade and at 6.6% in 2016/17 was second only to Queenstown Lakes.

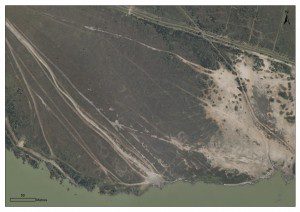

Vehicle damage on DOC reserve land at Halswell River

Recreation

Both historically (from at least the 1880s), and in contemporary times, Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere has provided for a wide range of water-based activities, e.g., trout angling, waterfowl hunting, whitebaiting, powerboating, windsurfing, rowing, kayaking and swimming. Land based acitivites within the lake’s environs include cycling, picnicking, bird watching and walking. However there is very little data on numbers of recreational users on or around the lake, or on the quality of their experiences. The most recent and ‘definitive’ work on recreation has been undertaken by Espiner et al. (2017). The state of recreation is much reduced across almost all categories compared with the levels of use in the 1970s and earlier. Reasons for this reduction are varied and include water quality issues. Vehicle access and associated damage to sensitive and important native plant communities is still an issue.

Tuna – eel (Photo Craig Pauling)

Horomaka Kōhanga- Supporting improved mahinga kai outcomes

Te Waihora is of outstanding significance to Ngāi Tahu Whānui, being a major source of mahinga kai (food gathering), both traditionally, and continuing to the present day. The most highly valued mahinga kai from Te Waihora are the native fisheries, particularly pātiki (flounder), tuna (eel), inanga (whitebait), piharau (lamprey) and aua (yellow eyed mullet). The importance of the fishery is highlighted by the original name for the lake – Te Kete Ika a Rākaihautū (the fish basket of Rākaihautū – the famed Waitaha ancestor). A key element of the 2005 Te Waihora Joint Management Plan was the creation of the Horomaka Kōhanga – a non-commercial fishing area at the Banks Peninsula end of the lake. It’s intent was two-fold – firstly, to help provide refugia for significant native fish species, and secondly, providing a place where mahinga kai or customary fishing activities could be more successful. Although commercial fishing is not allowed inside the kōhanga, fish can move freely in and out and can be captured outside the area.

In Lake Nutrient Processing

Research funded by Whakaora Te Waihora and Environment Canterbury has been examining how Te Waihora processes the nitrogen and phosphorus loads entering the lake. A research team have studied how nitrate is transformed in the lake to harmless nitrogen gas and how the historical build-up of phosphorus in the lake’s sediments still today contribute to fuelling algal blooms in the lake. The conversion of nitrate to nitrogen gas is mainly carried out by microbes in the lakes sediments under a variety of microbial processes – a key one being denitrification. Phosphorus can be released from the sediment under anoxic (low oxygen) conditions. A key finding of the research showed that during summer, the lake surface frequently becomes completely oxygen depleted, therefore allowing phosphorus to be released into the water column.

Kaitorete Spit

City to lake links

In June 2016 the Christchurch City Council resolved to join the Te Waihora Co-Governance Group. In addition to elected member representation in the Co-Governance Group the City Council also has representatives on the technical staff advisory group to the the Co-Governors, the Joint Officials Group. The City Council has an elected member on the Selwyn-Waihora Zone Committee and is a member of the Lake Opening Protocol Group. A proportion of Christchurch lies with the Te Waihora catchment, most of which is within the Selwyn-Waihora water management zone. Around the margin of Te Waihora within Christchurch’s boundary, the City Council owns 412 hectares adjoining the lakes margin on Kaitorete Spit and approximately 15 hectares of lakeside wetland beside the Rail Trail at Kaituna.

Discussion

Assessments of state have been provided in each topic section. Comparisons of these with 2015 results suggest that the conclusion then is still valid. However, while much has stayed the same, there have been both positive and negative indications this year. Two years ago a number of factors which we felt would contribute to improved breadth and quality of information about the state of the lake and catchment were identified. This included the development of a new comprehensive lake monitoring strategy. The benefits from the implementation of the comprehensive monitoring strategy, which provides a coherent framework for the collection of wide-ranging information on the resources of the lake and catchment, are not being realized. Success will require all agencies and organizations who have information-gathering responsibilities to provide leadership in their particular areas. Such a commitment will be enormously helpful in realizing the community’s aspirations for Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere and its catchment.

State of the Lake 2017

State of the Lake 2017